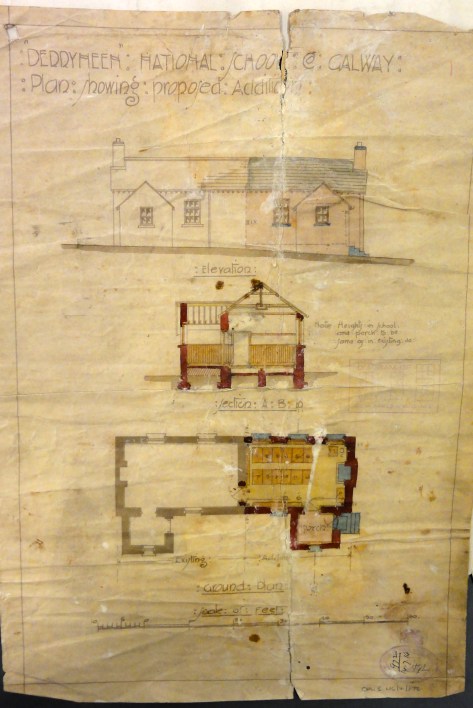

Brockagh National School, Brockagh Lower Townland, Co. Leitrim

(dated c.1885)

NGR: 201431, 337272

The little village of Glenfarne is located in north County Leitrim, surrounded by rolling drumlins and boggy lakelands that are so characteristic of this part of the country. The soil quality is poor, the lands are often damp and unproductive, and in recent decades, much of the landscape has been planted with vast expanses of commercial forestry in an effort to put the landscape to some commercial purpose. Leitrim is the least populous county in Ireland – often the butt of the joke in regional banter and rib-poking. But I don’t think anyone there really cares about that. In reality the county offers wonderful lakeside isolation, with forest-covered hills over-looking small hamlets, vernacular houses and ruinous clachains. It is a peaceful landscape, and though it can be harsh during a long winter of short evenings, in summer the still lakes glisten in the sunshine without the disturbance of excessive tourism.

The village of Glenfarne is probably best known as the site of the original “Ballroom of Romance”, which inspired a short story by William Trevor and was subsequently turned into a movie by the BBC. The story itself is a little grim; set in rural Ireland in the 1950s, the lead protagonist Bridie has been attending the local dance hall for years in the hope of finding a good husband who can help work her family’s farm. Now surrounded by younger prettier women at the dances, she comes to the realisation that all the good men of her generation have emigrated or have been spoken for; and her only remaining hope for marriage is with the alcoholic and unreliable Bowser Egan.

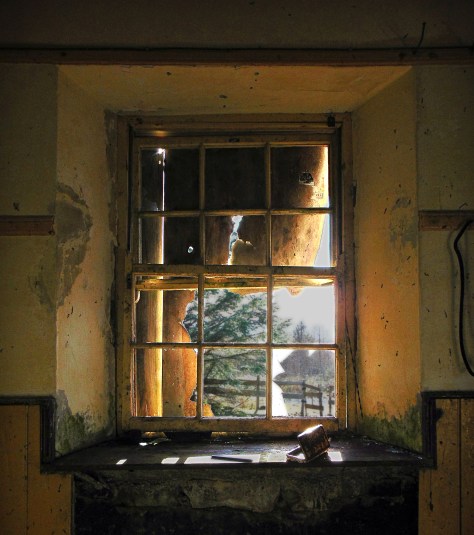

The story of The Ballroom of Romance is set in a landscape of rural decline and emigration – common themes of rural Ireland that are particularly strong in Co. Leitrim through the 20th century. Glenfarne was once serviced by the Sligo, Leitrim and Northern Counties Railway line from Eniskillen to Sligo. The line opened in January 1880 and finally closed on 1 October 1957. A sawmill and creamery operated adjacent to the railway line, and a tourist hotel was located in the adjacent townland of Sranagross. And just to the south of the railway in the townland of Brockagh was the the old two-roomed school house – Brockagh National School, built in 1885, but now empty and abandoned. Continue reading Brockagh National School, Brockagh Lower Townland, Co. Leitrim