Modernising National School design during the mid-20th Century – Basil Raymond Boyd-Barrett – Architect of National Schools for the Office of Public Works

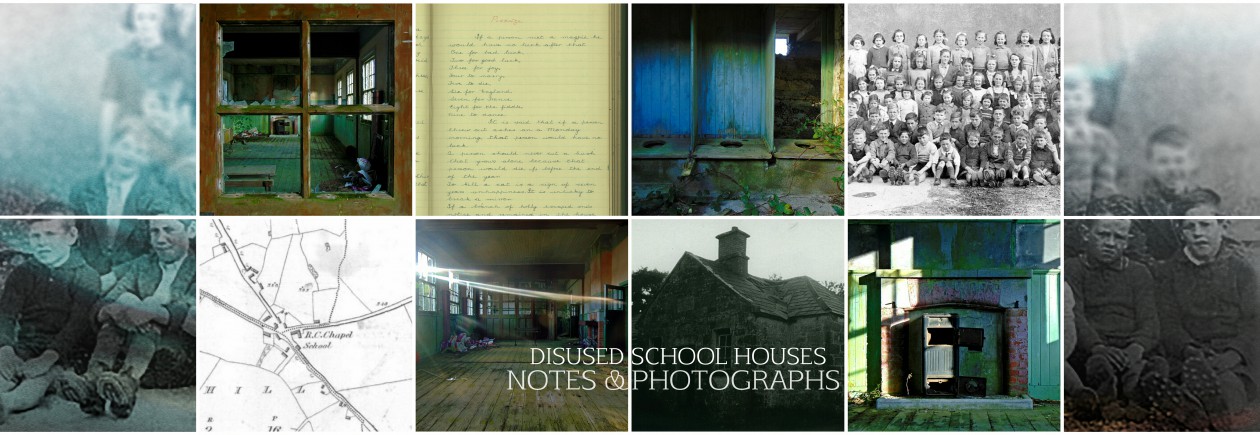

*There is a clear but difficult to define distinction between National Schools built in Ir eland during the 19th and early 20th century, and those that would be built from about the 1940s onward. Early school houses built by the Office of Public Works (OPW) had a vernacular feel to their aesthetic and environment. The earliest schools were run by the great religious orders in the Middle Ages and those were invariably built close to the church or monastery in the ecclesiastical manner, a style which persisted long after the strictly religious character had waned and indeed even down to comparatively recent times. Many are familiar with the early school with the high Gothic windows and gates, high ceilings with exposed root trusses, all looking like something between a parochial hall and a church and certainly more suited for either purpose than that of a school. It is not unusual to still come across such schools today and, where they have been erected as a National School, one finds that they were built as Model Schools about 150 years ago, or that they were erected by some enlightened Lord of the manor to provide education for the children of his tenants and workers.

From the 1830`s national schools were built to a standard plan based on pupil numbers. The first schools were of a very simple nature, consisting merely of class halls. An awakening of interest in public health towards the end of the 19th-century lead to general improvements in standards through the development of sanitary services such as toilet facilities.

However, in 1934 an architect named Basil Raymond Boyd-Barrett with a particular interest in school design was appointed an assistant architect in the OPW. In 1947 he was appointed chief schools architect, and his impact on school design in Ireland can still be seen today.

Basil Boyd Barrett (1908-1969) was born in Dublin on 19 September 1908. Brother of James Rupert Boyd-Barrett, both siblings would leave an indelible mark on Irish architecture through the 20th century. Basil was a student at the School of Architecture at University College, Dublin for two years, and attended the School of Art for four years. After serving as an apprentice at the office of Jones & Kelly, he would serve out the majority of his career at the Office of Public Works.

Barrett took an interest in school design beyond the scope of just bricks and mortar. In 1952, he presented a paper to Architectural Association of Ireland outlining in detail, the history of education in Ireland, and identifying the origins of school design in less-than-practical ecclesiastical architecture. His work with the OPW from 1940s onward would demonstrate a movement away from the form of the vernacular school house, for better or for worse. His approach to design seems to have sought to combine functionality and the aesthetics of form, with the practicality of providing Generic Repeat Design (GRD) schools.

When identifying a school designed by Boyd-Barrett it is important to remember that no two schools had the same plan yet each school could be compared to the next when examining its component parts (Butler 2013). There was individual architectural judgment invested in each school building yet they were all built in accordance with a specified type. The constitutional provision of equal educational standards to all pupils in the state, regardless of location, had led to the formation of and obedience to national standards for educational building.

What constitutes typical Boyd-Barrett design? Boyd Barrett’s original approach to ‘type’ was that fundamentals such as light, exercise and fresh air are provided to a minimum standard through the provision of defined component parts. How they fitted together depended on contextual issues and specific architectural judgement (Butler 2013). The component parts of the plan were arranged for the most part in a single stand-alone building on a green-field site. They comprise a single-story classroom block, usually with a pitched roofed and a lower circulatory block attached containing cloakrooms and toilets, usually flat roofed. Covered open shelters mostly removed from the main school block, supported on masonry walls and circular columns framed the external play space. In later years a water storage tower provided a vertical counterpoint to the horizontal arrangement of the school complex to complete the composition that is now infamous with primary education in rural Ireland.

Boyd Barrett`s generic school ‘type’ was defined as a kit of distinct parts. Each component part was specified; width, height and aspect of classrooms, down to the varying distances between coat hangers in male and female cloakrooms. It was the looseness in the arrangement and the coming together of the individual parts that lead to its successful universal application.

It was not until the 1930`s that recreational facilities came to be accepted as an essential requirement for rural schools under Boyd-Barretts influence. They came in the form of a covered shelter accessed directly from the school which opened onto a surfaced play space.

Circulatory accommodation between classrooms became centralised to a single corridor which ran the length of the classroom block with individual access to each classroom. Cloak rooms, wash hand basins and an externally accessed fuel store are placed at the ends of this circulatory corridor beneath a lower flat roof. Storage tanks and wash hand basins seen in the plan, filled with water collected from this flat roof, provided the only integrated sanitary facilities for students. Toilet facilities remained separated from the school block. The assumption is that the unpleasant smell from the un-flushable latrines justified their isolation at the furthest edge of the site removed from the school building.

The water tower was generally functional. Its mass concrete walls contained a tank at a high level which was the entire size of the base. An external ladder fixed to the outside of the tower provided access to the tank through an opening in the flat concrete roof. Later versions of the water tower housed an independently sealed steel tank with access up through the tower itself. The towers presence in all rural models due to a lack of a centralised supply, explains why it is now a strong part the schools rural monumental status that was outlined in “A Lost Tradition” by McCullough and Mulvin.

A very distinct and somewhat unexpected feature of Boyd Barrett’s design was the over-sized twelve-pane sliding sash Georgian windows which allow light deep into the plan of the classroom block.

For the majority of the schools built in this style around Ireland at this time, ornamentation of stone detailing was reserved to a limited application. Boyd Barrett outlined that the entrance way to the school should be laid out “as to afford space for an ornamental plot for flowers and shrubs in front of the school (Butler 2013). These plots were incorporated with door openings and provided the limited ornamentation required (see images of Drumlish National School below). It provided a welcomed break from the simple pallet of materials and the horizontal nature of the smooth plastered plinth and flat roof. A lower concrete canopy provided shelter over the doorway.

In an interesting feature of Boyd Barretts design, desks were to be arranged so that the main windows are on the left of pupils. This would suggest that this was to eliminate the casting of shadows for the preferred right handed student (Butler 2013).

Another component part of all plans was the externally accessed fuel store which was originally used to store solid fuel for the open fire or stove in each school. Later the room appeared to convert to the ideal place to locate the centralised boiler which provided heating in the smaller schools from the late 1960`s onwards.

*The above text heavily relies on Butler, J. 2013 Type Versus Model in School Design – with reference to OPW built National School in Ireland, under the reign of Basil Boyd Barrett as Chief Schools Architect

If you or someone you know attended these national schools, or if you have any further information – please do get in touch and share any stories, anecdotes, photographs, or any other memories you may have. If you know of further schools that I could visit, please do let me know. If you would like to purchase the book The Deserted School Houses of Ireland, visit the shop page here.

References

Boyd-Barrett, B. 1952 ‘Notes on School Planning, In Irish Builder and Engineer No. 8 April 12 1952

Butler, J. 2013 Type Versus Model in School Design – with reference to OPW built National School in Ireland, under the reign of Basil Boyd Barrett as Chief Schools Architect MArch Dissertation University College Dublin

McCullough, N. and Mulvin, V. 1987 A lost tradition; the nature of Architecture in Ireland. Ganore Editions, Dublin

Hi Mr Enda O’Flaherty,

We have an old school that closed fifty years in west Wicklow , a new roof and was painted last year ,and it’s used as a parish centre . If you are in this part of the country maybe you would call and see it.

The school is in Davidstown, Donard Co. Wicklow. Sorry don’t know the eircode. The committee enjoy your program on RTÉ.

Regards

Catherine Walshe

LikeLiked by 1 person

In 1945 I started school in Mountcollins, Co. Limerick. It was a mile from the village on the road to Tournafulla on Daniel Mick’s farm. Only a plaque marks the location now. It was a high, unplastered, stone wall, double building – Girls’ and Boys’ – with slate roof. There was little space around it and was entered through an iron gate and steps. The girls’ section had been closed and all three teachers shared the large, co-ed, open space that made up the original boys’ section. It was replaced nearby in 1949 by a school of the Boyd-Barrett design that did not need a water tower.

LikeLike

Take a look sometime at the old primary school in Templemore, County Tipperary. It appears to have been adapted from an original post-Penal Laws vernacular church (probably originally thatched). At some point central heating was provided. Today it is a social centre. I’ve not been inside the building since 1962.

LikeLike