Carrigagulla National School, Carrigagulla townland, Co. Cork/Scoil Carraig an Ghiolla, Co. Chorcaí

(dated 1934)

NGR: 138313, 084161

The parish of Macroom in Co. Cork is situated about halfway between Cork city and Killarney on the modern N22 roadway. Each day, significant volumes of traffic pass through the town of Macroom, with drivers unaware perhaps, of the locality’s rich and diverse cultural landscape. Crossing the River Sullane, the charred and imposing ruins of Macroom Castle overlook the the river below. Within the town, Macroom Market House (built c.1820) is a focus for remembrance, with many memorials and commemorative plaques including one to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the granting of market rights to the town of Macroom by Queen Anne on 30th September 1713.

There are few counties to rival Cork for the scale of its post-medieval and industrial heritage. But exploring the area around the parish in search of a disused school house in the townland of Carrigagulla, it was an obscure and understated industrial project from the mid-18th century that attracted my attention.

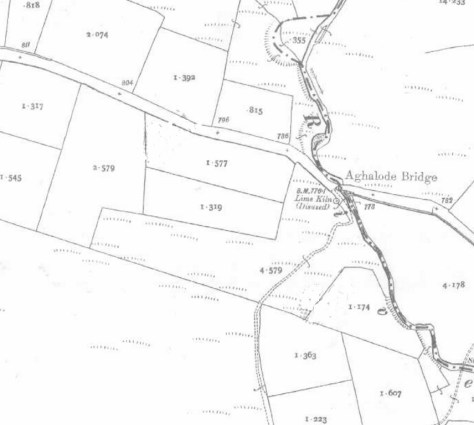

The townland of Carrigagulla is surrounded by the amphitheatre of the Boggeragh Mountain foothills. Here in the townland, adjacent to the Millstreet-Rylane roadside, are the ruins of Carrigagulla National School. But the Millstreet-Rylane roadway has its own story to tell about life in this rural area through the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Cork-Tralee turnpike road, better known as the ‘Butter Road’ was completed in 1748.Its construction was undertaken by John Murphy of Castleisland, who constructed the 56 miles of road including nine large bridges, 15 small bridges, toll house and turnpike gates. It was a requirement of the construction that the road be 30ft (9.14m) in width with drainage ditches and a 15ft wide (4.57m) gravelled surface. It became the main route by which farmers from Kerry and western Cork took their butter to the Cork Butter Exchange in the city (Rynne 2006, 317).

The turnpike system had been introduced into Ireland in 1729. Intended to provide good inter-county roads, turnpike roads were built and maintained by turnpike trusts which were generally run by local landowners. The turnpike act empowered named trustees to erect gates and toll houses on the roads and provided a loan for their construction. The toll monies, collected from all but pedestrians and local farmers who used the roads daily, were intended to maintain the road and repay the loan (ibid., 315).

The Cork-Tralee turnpike road is today but a back-road, with the majority of traffic passing along the N22 between Cork and Kerry. The area is quite, the hills are largely forested, or bare and boggy, and the once bustling highway is often empty of traffic. However, at Aghalode Bridge, and adjacent to the Aghalode River, there is an old school house that is perhaps a reminder of a more thriving time in this rural spot. On the west side of the Butter Road you’ll find the remains of Carrigagulla National School/Scoil Carraig an Ghiolla.

Constructed in 1934 it is a simple, detached, two-bay, single-storey national school on a T-shaped plan, having a gabled projection to the centre of the east elevation.Though still roofed, it is in a poor state of repair. From the outside the building is certainly institutional in appearance; the rough grey rendering is not inviting, the surrounding schoolyard is overgrown, and the foreboding hum of a wasp’s nest deters visitors. The dull-green, pealing paint on the window frames and rainwater goods only seem to emphasise the buildings predicament. A squadron of wasps emerge from the brickwork chimney stacks and air vents as I get a little closer.