In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, professional opportunities for women were, realistically, greatly restricted. Nonetheless, Irish girls and women of all social classes were leaving home to take part in public life – work, schooling, buying and selling, activism and entertainment. National school teaching was considered a great career opportunity for girls from skilled working-class and small-farming backgrounds in Ireland. On-the-job training was sometimes paid, and scholarships were increasingly available. Thus, the burden on low-income parents was bearable.

Unlike other positions in the civil service at the turn of the twentieth century, national school teaching was a lifelong job; the marriage bar was introduced only in 1933 for those qualifying on or after that date. At this time, the National Board put great emphasis on teacher training. Ireland was not short of teachers or schools: anyone could open a school and expect a modest income. This work was considered suitable for women, whether single or widowed. If they knew how to read and write, they were considered equipped to teach. Furthermore, the business of education was thriving through the 19th century; the figures below indicate the exponential growth in the opening of national Schools through the 1830s and 1840s in Ireland:

Year No. of Schools in Operation

1833 789

1835 1106

1839 1581

1845 3426

1849 4321

The teachers were at first treated and paid like domestic servants or unskilled labourers and they often had to approach the parish priest via the servants’ entrance. Their pay was from the Board minimum, ranging from £5 a year to £16. These low figures can be explained by the informal understanding that, once appointed to a teaching post, a teacher could expect further contributions gifted from local sources. In 1858 the National Board claimed that it was paying 80 per cent of teachers’ salaries, and inspectors told teachers that if they wanted more they should apply to their own managers (i.e. the clergy). This ignored the fact that the manager could dismiss a teacher at a quarter of an hour’s notice. It was recognised on all sides that teachers would have to supplement the basic allowance. Predictably, all this was blamed on the government, not the local managers.

The standard of education in boys’ and girls’ secondary schools rose in the second half of the nineteenth century, especially after the passing of the Intermediate Education Act (1878) and the admission of women to universities following the opening of the Royal University in 1880. By 1900 candidates for teacher training would have passed the Intermediate Certificate at about the same standard as a university matriculation. By 1900 half the newly appointed teachers had been to a training college; the other half had at least served some time as monitors or pupil teachers/teacher’s assistants. The latter could normally be only assistant teachers, though in a two-teacher school that was an important office, often involving teaching all the girls.

The standard of teacher training was not homogeneous through the 19th century. In 1834, three years after the establishment of the national system of primary education in Ireland, the first Model School was opened in Upper Merrion Street, Dublin. Model Schools were teacher-training institutions under the auspices of the Commissioners of the Board of National Education, the administrative body of the national system. Each Model School maintained at least one national school where student teachers could practice their skills and gain experience in teaching. These training institutions were numerically insignificant, never exceeding thirty as opposed to the thousands of ordinary national schools. It was originally intended that only male students would be trained for the office of teacher at the Model Schools. Female student teachers were not accepted until 1842.

The idea of creating a Model School was first entertained in Lord Stanley’s letter to the Duke of Leinster, on the Formation of a Board of Commissioners for Education in Ireland of 1831, which outlined the terms of the proposed national system. The Board of National Education was charged with the task of “Establishing and maintaining a model school in Dublin and training teachers for country schools.” Years later the commissioners of the board defined the fundamental objectives of an archetypal Model School as follows:

- To promote the united education of Protestants and Roman Catholics in Common schools

- To exhibit the best examples of National schools

- To give a preparatory training to young teachers

However, as with most systems and institutions in Ireland during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Catholic Church was dominant and controlling. The bishops refused to accept a training college not controlled by themselves with the result that in 1900, 70 years after the national school system was established, only 48 per cent of the national teachers had received any formal training. As early as 1856, the Sisters of Mercy in Baggot Street, Dublin, made efforts to give short courses to women teachers, but the six-month course was dismissed by the Powis Commission on Education as totally inadequate. In 1870 the commission recommended the allocation of public money towards private (denominational) training colleges. In 1883 St Patrick’s Training College for men and Our Lady of Mercy Training College for women were opened and recognised, but had to support themselves. Government assistance was later allowed in 1890.

By the 1950s, female teachers outnumbered male teachers two to one. All this time, and almost to the present day, pay for teaching was not equal between women and men. Through the nineteenth and twentieth century all primary schools were Church-run. The overwhelming majority were managed by the Catholic parish priest, with the rest by the local Church of Ireland parish. Successive education ministers reiterated their support for, indeed insistence on, Church control of education. This ‘Catholic ethos’ had a dreadful impact on the education of girls. Only a small number of girls were allowed to aim for higher education. Most were taught to read and write, sew, cook and pray.

Women were educated to be wives and mothers. This education began from the day they started school. As late as 1985 the curriculum at primary level stated that: ‘Separate arrangements in movement training may be made for boys and girls. Boys can now acquire skills and techniques and girls often become more aware of style and grace … while a large number of songs are suited to boys, for example, martial, gay, humorous, rhythmic airs. Others are more suited to girls, for example, lullabies, spinning songs, songs tender in content and expression.’ The gender-segregated nature of many Irish schools is part of the legacy of the denominational origin and control of education since the nineteenth century. However, even today, Ireland is unusual in a European context in that a large number of schools are still single-sex institutions at both primary and second level (42 per cent of second-level students attend single-sex schools, the majority of these being girls’ schools).

In terms of extracurricular activities in the past, music and arts were traditionally encouraged to a greater degree in single-sex girls’ schools, while sports (particularly field and contact sports) were of greater importance in boys’ schools.

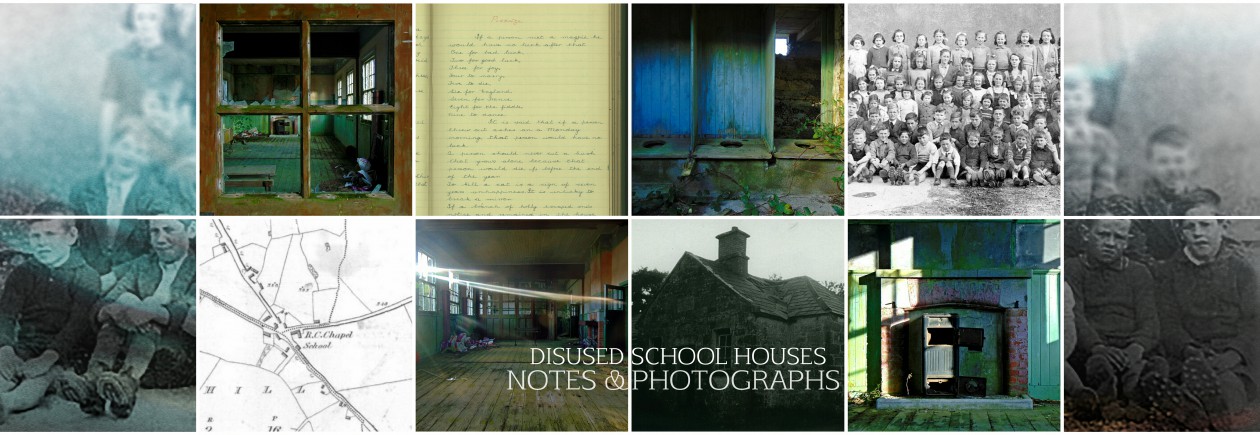

There was a shift in emphasis in the 1960s from education as a social expenditure to an investment in the individual and society as a whole, and an economic boom facilitated increased investment and interest in education. Increased contact with organisations such as the UN, UNESCO and the OECD removed the insularity that had characterised Irish educational policy since the 1920s and facilitated a growing realisation of the need to invest in education for Ireland to compete on an increasingly international stage. However, although gender-segregation is much less common today, the architecture of many nineteenth- and twentieth century school buildings still in use reflect the former division. Certainly, the majority of the schools that I have photographed echo the past paradigm of firm gender segregation. Now seen as archaic and outdated, was there ever any merit to this canon, or was it simply another reflection of denominational control of

the Irish education system through the decades and centuries?

If you would like to purchase the book The Deserted School Houses of Ireland, visit the shop page here.

Horgan, G. (2001) Changing women’s lives in Ireland International Socialism Journal Issue 9

Keenan, D. (2006) Post-Famine Ireland: Social Structure: Ireland as it really was. Xlibris Corporation.

Mangione, T. (2003) The Establishment of the Model School System in Ireland, 1834-1854. In New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua Vol. 7, No. 4 (Winter, 2003)

O’Donovan, B (2103) Primary School Teachers’ Understanding of Themselves as Professionals PhD Thesis, Dublin City University, Dublin.

Why is there no mention of the church of ireland training college which opened in 1884? this seems very one sided to me. A man was brought over from England and he set.up.monitorial teaching, where a teacher taught a small number of pupils and each pupil went on to teach a number of other pupils.

LikeLike