This week (August 20th – 28th) marks National Heritage Week in Ireland. It is a multifaceted event coordinated by The Heritage Council that aims to aid awareness and education about our heritage, and thereby encouraging its conservation and preservation. As part of Heritage Week 2016 there are daily posts to the Disused School Houses Blog and this is the fifth post in the series.

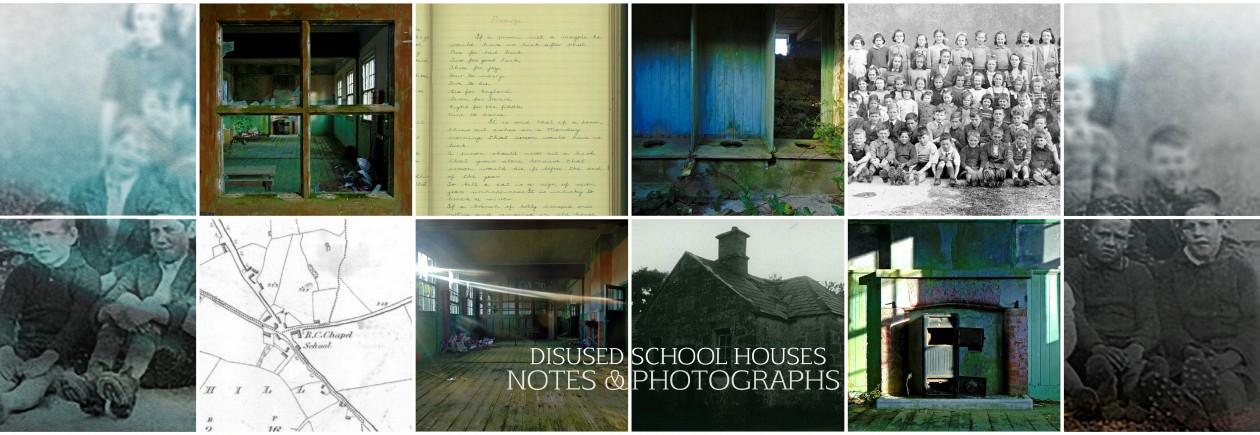

For the past two years I’ve been casually photographing abandoned school houses around Ireland. I don’t have any explanation for why I began doing this, but this hobby started by accident with no real projected outcome. I uploaded a few of my snaps to this blog and from there the project began to develop with a view to publication in the coming months. Matching my images with stories recorded in these abandoned schools by the Irish Folklore Commission in the 1930s, the now-empty buildings came to life once more.

To-date, I have photographed about 90 schools in 20 counties in Ireland. Through the process of photographing these buildings and later researching the schools and their former hinterland, I have been considering their greater significance as relics of disappearing rural Irish lifeways. A number of patterns have emerged in their numbers and distribution, and so below I’ve written a few paragraphs offering my opinion on the proliferation of empty school buildings across Ireland. (I have also added some of the better images from the past few months, just to keep your interest).

There is no doubt that there is a greater proliferation of abandoned schools in more rural and depopulated areas, with a near absence of them in urban centres. To begin explaining this let’s start with the establishment of the National Schools Act in 1831;

In 1831, Earl Stanley, Chief Secretary for Ireland, outlined the new State supported system of primary education (this letter remains today the legal basis of the system). The two legal pillars of the National School system were to be (i) children of all religious denominations to be taught together in the same school, with (ii) separate religious instruction. There was to be no hint of proselytism in this new school system. The new system, initially well supported by the religious denominations, quickly lost support of the Churches. However, the population showed great enthusiasm and flocked to attend these new National Schools.

In the second half of the 19th century, first the Catholic Church, and later the Protestant churches conceded to the state, and accepted the “all religious denominations together” legal position. Where possible, parents sent their children of a National School under the local management of their particular Church. The result was that by the end of the 19th century, the system had become increasingly denominational, with individuals choosing to attend schools primarily catering to children of their own religion. However, the legal position de jure, that all national schools are multi-denominational, remains to this day though in actuality, the system unfortunately functions much like a state – sponsored, church – controlled arrangement (this is an argument for another day).

Putting these facts in context, let’s look at what was happening in Irish society through this time. Shortly after the establishment of the National Schools Act, Ireland’s population began to decline dramatically, initially triggered by the Great Famine of the 1840s. Between 1840 and 1960, the population of the 26 counties of what would become the Republic of Ireland fell from 6.5 million to 2.8 million. However, this decline was driven by mass emigration, and birth rates in Ireland during this time were amongst the highest in Europe. Because of this fact, despite a dramatically falling population, the need to educate significant numbers of children of school-going age remained. New school buildings continued to be required and used. There were particular spikes in new-builds after the National Schools Act in 1831, and again 1926 with the School Attendance Act which meant parents were legally obliged to send their children to school for the years between their 6th and 14th birthdays.

During this time the Irish demographic was quite different to today’s, with the majority of the population living in a rural setting. In a time before motorised transport and a transport infrastructure, the requirement was for many small national schools which local children could walk to. Hence, in 1950 there were 4,890 national schools staffed by 4,700 male and 8,700 female teachers (CSO) in the 26 counties, while the population remained at about 2.8 million. In 1998 with the Irish population passing 4 million, the number of open national schools was 3,350.

How is it that with a rising population, there could be less national schools in Ireland? To explain this, we can look at the change in the Irish demographic from about 1950 onward. Through the 1950s, some 400,000 Irish emigrated because of a lack of opportunities for employment at home. With things at their most bleak, at the beginning of the 1960s the programme for economic expansion was initiated, establishing the Industrial Development Association (IDA) which sparked an improvement in the Irish situation, the development of an industrial economy, and a shift in settlement patterns from a rural based economy to one centred around industry and urban settlement. This saw the beginning of an emptying of the rural Irish population into the larger towns and cities. Small farms began to be consolidated. Further to this, actions such as the ‘evacuation’ of many offshore Islands compounded the issue even more.

All the while Ireland’s birth rate began to drop, becoming more like that of the rest of Europe.

Joining the EEC in 1973, Ireland was now beginning to resemble it’s European neighbours in terms of demographics. Further to this, motorised transport became more widely available and so the hinterland of small schools became wider, with many schools in rural areas being consolidated into larger multi-classroom school buildings while the smaller school houses were closed and left to rot.

There are some areas where these factors were more pronounced. Areas of poor quality land which could not support a large population were heavily depopulated in favour of urban living. Areas such as West-Cork, Kerry, Connemara, Mayo, Leitrim, Roscommon, Donegal and the Midlands saw the greatest decline in the numbers of young people remaining at home. And with this being the case, the local birth rates dropped further.

The factors outlined above help to partially explain how, through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, many small rural schools were shut down and why in rural Ireland there are so many abandoned school buildings. In short, it’s a story of changing demographics, emigration, depopulation of the rural countryside, and the changing requirements of rural settlement. During the period 1966-73, the number of one and two teacher schools was reduced by c.1,100. Did this decision to close so many rural schools have a positive or negative impact on the rural Irish landscape in isolated areas? I’d love to hear your opinion.

So glad you found an “accidental” hobby. I really enjoy the posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Karen, thanks for checking out the Blog!

LikeLike

A very thoughtful and informative look at the complex socio-historical factors. It’s interesting how so many schools seem to be in the middle of nowhere, the community since disappeared. Sadly small schools are still in danger in rural areas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Freespiral2016! Hope the holy well hunting is going…well

LikeLike

Fascinating background to the photos. I really enjoy what you’re doing here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Fiona. Very much appreciate you taking the time to read my blog

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely post. Do you have any kind of map of the schoolhouses you’ve photographed? I think it would make for an interesting roadtrip.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Shane. I do but I’m holding it back for a little while until I have photographed all the schools I intend. There are grid coordinates at the top of each post to help you track them down. Thanks for your compliment and for taking the time to read the post

LikeLike

Very nice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Enda:

What you are doing is so worthy — thanks so much.

Pat Flaherty

LikeLike

Thanks so much Pat. That’s a very lovely comment. I really appreciate your comments and you keeping I’m touch. Enda

LikeLike

Thank you! I enjoyed both the photos and the interesting information. I believe my great great grandmother, Catherine Geoghegan, was a teacher, along with her husband, Patrick Geoghegan, at Ballymintan, County Roscommon in the 1860s. We were shown the abandoned school house in 2010 by a former student (77 yrs old). We were unable to get near the building due to the nettles (which love me!!). I wonder whether you might have any photos or info on Ballymintan National School, not far from Ballinasloe, which you could post? Thanks, again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Sheila. I’m afraid I don’t but I’ll be sure to check it out next time I’m up that way. Thanks for the info and I might be in touch in the coming weeks if that’s okay?

LikeLike

Hi, again. Just came across our posts while reviewing records and thinking about another trip to Ireland. I hope you are still doing your great work and might yet get photos and information on the former National School in Ballymintan. Wishing you the best. Sheila

LikeLike

Hi Sheila – yes, I’m making plans for the coming year for more photography after a few months off. Ballymintan is on the list!

LikeLike

HI Enda, Am now reading your informative and interesting essay . I am the owner of a large (one-room) National School at KIlnaboy at the edge of the Burren in Co Clare. Over 80 pupils attended here in the early 20th Cet) .The school was built in 1884 and vacated 1952. The structure is still in pretty good order, though time is taking its toll. However, I will soon have to put it on the market as its upkeep is a drain on my limited available funds I enjoyed reading of the other such structures that dot the landscape. Many thanks.

LikeLike

Hi PJ. An amazing coincidence, but I’ll be passing Kilnaboy tomorrow. Are you around?

LikeLike

Really interesting post, thank you, and your photos are excellent. We moved to a small village in Clare when we left Bray, county Wicklow, in the early ’80’s and we had two young children at the time. The school there had been struggling to keep a fourth teacher because of the decline of its population. The teachers were delighted when we told them that not only had we two children to add to their numbers but we were also expecting twins. I was amazed at how much it meant to a small village to have a family of six move in.

LikeLike

Hi Jean. Thanks very much. I’ll have a post about a school house in Clare later in the week as it happens. Yes, even just a handful of extra school children can make a difference in some areas. Thanks for checking out the blog. Your input is much appreciated

LikeLiked by 1 person

My question ,why were they left to rot and not sold or purchased by

others. The setting was always local and were habitable?

LikeLike

Hey! Thanks for getting in touch. Each case is different but I guess in many cases, the local population was in decline and the property might have been difficult to sell. Also, I guess sometimes the land a school was built on may have been in the possession of a local trust or the church which might complicate sale

LikeLike

Just spotted one of your photos on Twitter …. really eerie shots …. they remind me of when I was in Waterford some time ago came across the wife’s Aunties house abandoned in the middle of nowhere – the roof had gone but all the rooms could be identified …… childhood was frozen in time ….. it must be an Irish thing and a lack of rural population that allows such buildings to remain and not “recycled” …….

Adrian Hobbs Bowes England

LikeLike

Hi Adrian. Thanks for your comment and for checking out the blog. It’s a combination of factors really. If you’re interested, try the post I have written about why there are so many abandoned national schools scattered across the rural Irish landscape. You’ll find it under the miscellany tab

LikeLike